Traveling west with Mack Varner is a diversion from the ordinary

Published 6:10 pm Friday, April 3, 2020

Whenever Mack Varner plans a weekend camping getaway, he does it right.

He assembles a small crew of friends. He gathers supplies, plots out logistics, and finds a good spot to explore. Then he hands out books.

“We’ll have to do homework because he’ll quiz us on it,” laughed Bob Morrison, a frequent companion on Varner’s adventures.

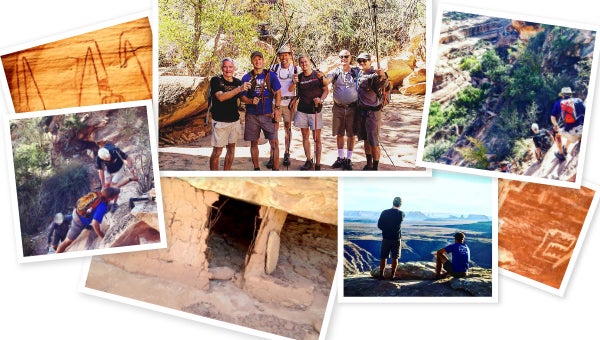

The extra study is required because Varner’s camping trips are not your ordinary weekend in the woods. Three or four times a year he heads to Southeastern Utah, to an area named Cedar Mesa, with about a half-dozen people to explore ancient cliff dwellings and the rock art left by the Anasazi people that lived there a thousand years ago.

Varner, a Vicksburg attorney, has been making the trips for about 15 years and estimates he’s gone “25 or 30” times in that span with more than two dozen people total.

“It’s just something different. It ain’t Disney World. It ain’t skiing. It’s nature and wilderness at its best,” Varner said. “I think it’s a passion. I’m planning on going three or four times this year. You can go on Thursday and be back on Monday. It’s an easy trip.”

The 75-year-old Varner has long been an outdoors enthusiast and active. He’s run more than 150 marathons and became interested in the Utah ruins while backpacking and hiking in that area and nearby Colorado.

He read about Cedar Mesa and took an interest in it because it satisfied both his intellectual curiosity and sense of physical adventure.

Cedar Mesa is a 400-square mile plateau slightly northwest of the Four Corners region where the borders of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona converge. Mostly located in the Bear Ears National Monument and filled with canyons, natural arches and cliffs, Cedar Mesais a backcountry hiker’s paradise.

Tucked among the terrain are ancient cliff dwellings, artifacts, and pictoglyphs and petroglyphs left by the various civilizations that have inhabited and passed through the region over the last several thousand years.

The Anasazi inhabited the region between about 200 B.C. and 1500 A.D. They carved homes out of the cliffs — some resembling modern apartment complexes — or built small homes from mud and stone. Many of those features have been perfectly preserved by the dry desert air.

“Some of them are hard to get to. Sometimes you stumble on things that are not in any books,” said Vicksburg resident Dan Waring, who has been on about 20 of the expeditions with Varner. “There’s so much out there and it’s dry country, so it stays. You can find pieces of corn cobs that are three inches long that have been there for hundreds of years. You can see smoke-scarred ceilings. It’s eerie to think it’s 1,000 or 2,000 years old and now you’re seeing it.”

The rock art is the reason behind the homework Varner assigns to his companions.

Although their base is usually the same spot on Cedar Mesa, Varner does extensive planning to get the most out of each trip and see things none of them have before. In addition to books and articles on the subject, Varner has become an expert on backcountry navigation and maps as well as supply and logistics.

“There are no big signposts or maps. It’s all about research, reading (topographic) maps and knowing where the pictoglyphs are,” Varner said. “We’ve been so many times, but there’s still so much to do. What makes it so much fun is the route-finding. It’s not mountains like Colorado. It’s about hiking and finding. Besides rock art, it’s interesting to find the cliff dwellings, too.”

The research allows the group to efficiently use their limited time on the mesa and see as much as possible. The long weekend trips typically consist of a series of day hikes, anywhere from 4 to 8 miles in length, over rough terrain. Varner said he doesn’t go anywhere that would require climbing ropes, but small climbs along narrow ledges and steep cliffs are common.

“It’s not a hike in the woods. We do a lot of slick rock climbing,” Varner said. “If I’ve got to rope in, I’m not doing it.”

Injuries and hairy scrapes on the trips, Varner said, have been virtually non-existent. There was one night when the group had to evacuate their camp to avoid a flash flood, but Varner said the worst incident he’s ever encountered happened because of the local wildlife.

“The worst thing that’s probably happened to us was somebody buried the keys to the truck and a packrat had dug them up and taken them,” Varner said. “Somebody had to come get us. We had to break the windows to get into the truck. It was a horror show.”

More often, Varner’s groups get to see things few modern eyes ever witness. In some cases, it’s possible they’re the first to see something no one else has for hundreds of years.

“On one backpack trip through Salt Creek Canyon in Canyonlands National Park, it started raining. I noticed an overhang, and I was scraping out a place to put our stove. I found pottery shards. We weren’t the first ones there. We covered it up and put the stove somewhere else,” Varner said. “The trails we’re doing now, I don’t know if everything has been seen or not. We find some rare and remote art.”

It’s those sorts of experiences, Varner said, that keep him going back out to Utah. He went four times in 2019, including one solo trip, and has several visits planned for 2020.

He’s also spreading his passion for the place to others, sharing the joy and wonder of exploration and history for one of the United States’ unknown gems.

“That’s a rare feature of this place. There are so many details that you don’t have time to see it all,” Morrison said. “You go back with the notion that you might find something somebody hasn’t seen in 800 or 900 years. It’s infinitely interesting. Every time you take a turn in a canyon you see something interesting.”