Old Mississippi River Bridge still stands strong at 90

Published 3:44 pm Tuesday, May 12, 2020

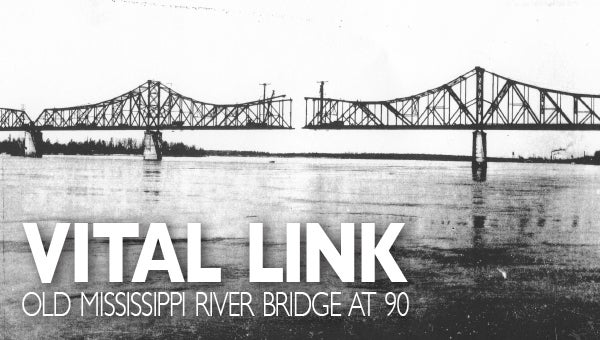

- A central gap in the Old Mississippi River Bridge sits waiting for the final piece to complete construction of the bridge, which was opened to traffic in April 1930. The bridge was replaced n 1973 by completion of the Interstate 20 bridge. (Photo courtesy of the Warren County Bridge Commission)

For 68 years, from the day it opened in 1930 until it was closed to vehicle traffic in 1998, the Old Mississippi River Bridge — or officially, the old U.S. 80 bridge — provided a crucial link for residents between Vicksburg and Louisiana.

“Dating back into the early 1900s, the bridge was the largest impact to this area and this state — both to Louisiana and Mississippi, but more to Mississippi, because it did open up that whole idea of being able to drive from one bank to another without having to use the ferry,” bridge superintendent Herman Smith said.

For several years, he said, the 90-year-old bridge was the first and only bridge south of Memphis, Tenn., crossing the Mississippi River.

“When this bridge opened up in 1930, there were no other bridges south of Memphis than this bridge; not even New Orleans or Baton Rouge,” he said. “The Huey P. Long Bridge (in New Orleans) didn’t go in until the 1934-35 area, and the Baton Rouge bridge, in ’37, ’38 or ’39, in that neighborhood. The Baton Rouge bridge was built similar to this one.”

The bridge’s history goes back to February 1926, when businessman Harry Bovay began talking about building a bridge across the Mississippi River. At the time, vehicle and rail traffic going from Mississippi to Delta, La. crossed the river by ferry.

Bovay in 1926 was able to get legislation passed in the U.S. Congress authorizing the Vicksburg Bridge and Terminal Co. to build the bridge, which now sits north of the Interstate 20 bridge.

According to a timetable on the bridge’s history, construction on the 15,966.9-foot span began in 1928 at a cost of $4.7 million, or about $71.13 million in today’s money. The bridge was opened to traffic in April 1930. Rail traffic began in May 1930 under a contract signed in 1927 by the Vicksburg Bridge and Terminal Co. and the Illinois Central Railroad.

The company had several problems during construction, Smith said. One of the first involved problems with pier 2, which is affected by a fault line, and “began moving right off the bat.”

The structure under the highway and railroad called bents (or leg towers) D and E started sinking almost immediately after they were built and the builders replaced the structure on the west side from the levee to the west approach with steel.

“They (the builders) built it originally as a wooden trestle, then they built it out of concrete; they changed the pier structure under it,” Smith said. “It cost less to build it out of wood, and they figured in that short a distance they wouldn’t need steel, but they wound up doing that.

“They spent a ton of money there as well. That was under the west approach right at the levee on the Louisiana side. They used about 1,530 feet (of steel) support legs that they had to put in concrete support legs underneath it instead of the wooden trestle.”

The Vicksburg Bridge and Terminal Co. later went bankrupt, and in 1947 the Warren County Board of Supervisors approved purchasing the bridge for $7 million, or $81.02 million in today’s money, using bridge revenue bonds.

In 1948, the Mississippi Legislature approved a bill establishing a five-member bridge commission to oversee the bridge, which remained open to traffic until the construction of the I-20 bridge in 1973.

Smith said the commission closed the bridge to traffic 1998 because the concrete was falling from two sections on the bridge’s west approach.

“Once they replaced those two sections of concrete, the bridge commission notified MDOT (Mississippi Department of Transportation) and LDOTD (Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development) they were going to open it to mostly local traffic, he said.

“MDOT was OK with it, they didn’t have a problem with it, but Louisiana said, ‘No.’ They didn’t want it open under any circumstances and they gave reasons.”

Louisiana, he said, “Never contributed one penny toward the maintenance of this bridge; it was maintained at one time by the Vicksburg Bridge and Terminal Co. After that, by the Vicksburg Bridge Commission of Warren County.

“We never received funds from LDOTD. They have never funded the bridge,” Smith said. “All they did was fund the road to the bridge.”

Smith said working on the bridge is different because one of the things he and the bridge staff do daily is looking for something out of place. “These guys look for something that stands out,” he said.

And while the bridge has received many barge strikes since its construction, he said, the span’s most serious problem is the movement of the bridge’s pier 2, which is affected by the fault in the earth about 200-300 feet deep that also affects the Interstate 20 bridge.

“The pier 2 movement is probably the thing that has caused it the most issues,” he said. “Pier 2 has moved between 30 and 32 inches from its original location in 1929. Where it used to be is not where it is today.”

While a 2-inch shift may not seem major, Smith said any shift in the pier has a major effect on the bridge.

“When I started here in 2002, they were resetting the bearings on pier 2 because the pier had moved so far, it was literally shoving the superstructure, the whole thing, to the west and was pulling the east approach off its bank,” he said. “They (contractors) had to reset the bearings, poured concrete on the side of the pier and set the bearings more eastward, which allowed everything to move again. We had to redo it in 2009 because it moved so much it had to be reset again.”

In March, Smith said, contractors completed a $950,000 project to repair issues caused by pier movement that was discovered in January 2019.