Tully Toys have continued to be a cherished treasure for many children

Published 11:23 pm Friday, November 20, 2020

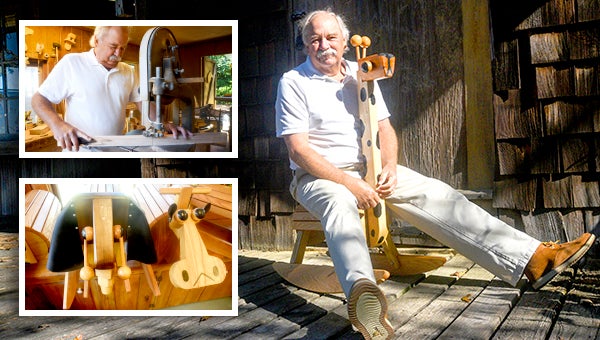

- Tully Hall, the woodworking creator behind the iconic Tully Toys. (Courtland Wells/The Vicksburg Post)

This feature on Tully Hall and Tully Toys is included in the November/December edition of Vicksburg Living. For information on how to subscribe to Vicksburg Living, call 601-636-4545.

A thin, but rather permanent, layer of sawdust coats the shop at Tully Hall’s home.

Open doors and windows and a Shop Vac can clear up some of it, but the tools and patterns on the walls have taken on an almost decorative yellowish hue. A puff of freshly powdered wood from the belt sander soon joins its predecessors and adds to a decades-long lineage.

Hall’s two-room shop is more than just his hideaway from the world. It is, all at once, a link to the past and the birthplace of new creations, a place where things are made to enjoy and to last. The 76-year-old Vicksburg resident has been making his wooden “Tully Toys” — handmade, wooden rocking animals — in these two rooms for nearly 50 years and is showing no signs of slowing down.

The toys have delighted children and adults alike as they pass them down through the generations or order new ones for their grandchildren.

“I’m getting a lot of orders that are second- and third-generation. People appreciate the quality they can pass on to their kids and grandkids,” Hall said. “Most people relate to a wooden toy from the old days, and they like something handmade. The production, price and style are all something people like to buy.”

A real woodman

Hall has spent his entire life in and around the forestry and woodworking business. His great-grandfather founded the Anderson-Tully Lumber Company, and Hall worked for 40-plus years with the company. During his early years he said he developed an appreciation and love for the craftsmanship that it took to turn raw wood into finished products.

“I always worked out in the woods, but I would go to the furniture factory after lunch and got to know those guys. They showed me how to do all of these things,” Hall said. “When I was in high school I worked at the mill and would go back to watch them make butcher’s blocks. The technology they used fascinated me.”

Hall worked primarily on the logging side of the industry, but in the early 1970s took up woodworking as a hobby. He started with furniture but did not enjoy it. Not only was it a more arduous task, but the pieces didn’t sell very well.

“For furniture, almost every one of them has to be a commission,” Hall said.

Instead, he started making wooden toys that had more mass appeal and turned it into a thriving side business.

The first batch of Tully Toys included a wooden elephant and giraffe for his nephew. Within a few years, he was making enough to fill a wooden zoo and selling hundreds of them a year at crafts fairs all over the United States. His toys sell for $65 each, which is the same price it has been for years.

“Back in the late 70s and early 80s I did a lot,” he said, before rattling off a list of cities large enough to fill the verse of a Johnny Cash song. “The best two I’ve ever been to were Sarasota and Kansas City. I would take 150 toys and put them in a U-Haul, and sold every one of them the first night.”

As he became a master woodworker, Hall also became a skilled salesman. He picked up different techniques from other craftsmen that helped him stand out from the crowd. One of his favorite tricks, he said, was making children cry.

“At a craft fair you only have so many minutes to get somebody’s attention. I would put 25 or 30 toys on the ground and let the kids play on them. The best thing is when you get the kids to cry or lock their legs because they don’t want to leave. That’s a sale for sure,” he said with a laugh. “It was a lot of trial and error, and rejection. If you go someplace and don’t sell them, you either watch somebody and learn or you’re not going to sell anything.”

The wooden zoo

Since making those first couple of wooden toys in 1971, Hall has refined his production process to make it quicker and easier while still maintaining the quality that is expected of a handcrafted masterpiece.

Although each toy is unique and built to order, they share the same basic parts. All of them have a saddle-like seat atop a pair of wooden legs and a rocker base made of red oak. The heads and other parts of each toy are made of ash.

So, whenever Hall receives an order of fresh lumber, his first piece of business is to spend a day or two turning it into the parts he’ll need later on. One of the two rooms of his wood shop contains a couple of small saws and sanders, as well as a joiner that he uses to trim 3-foot pieces of lumber to his specifications.

In addition to the standard bases, Hall has patterns for each of the 16 designs he builds. Having the pieces pre-cut and stockpiled allows him to assemble the animals in a couple of hours when an order comes in.

“All of the bodies are the same length, the rockers are the same length. I simplified it for production,” Hall said. “I don’t have a lot of tools. There’s a table saw, a joiner, a band saw, a whole lot of sanding stuff. It’s real simple and not a lot of expensive equipment.”

After a toy is built it moves across the deck to the “finishing shop,” where varnish and paint are applied. The finishing shop is a cleaner environment that, Hall said, prevents loose sawdust from drifting into the varnish. Adding the varnish and paint and giving it time to dry takes a day or two.

Hall has the patterns for 16 different animals. He started with those you might see on an African safari such as the giraffe, lion, hippo, elephant and rhino, but eventually added some with a more Southern flair like the armadillo, alligator, crawfish, razorback pig, chicken, cow and riverboat.

There are also patterns for a horse, dinosaur, ostrich and ram. Other designs have come and gone over the years.

“I had a few flops,” he said, with the tone of a man recalling an old love gone wrong. “I made a shark when ‘Jaws’ came out (in 1975) and it was terrible. Then we tried putting a toy chest in one of them. It didn’t work, because it was too heavy for the kids to move it.”

There is also at least one custom pattern he has that he seems like he’d rather forget. A customer who was a Mississippi State fan asked him to create a bulldog Tully Toy. Hall made it and keeps the pattern on the wall of the wood shop, but seems to have done it begrudgingly. His father Parker Hall, after all, was an All-American quarterback at State’s rival Ole Miss in 1938 and won the NFL’s MVP award with the Cleveland Rams in 1939.

“There’s that bulldog,” Hall said, his voice a touch lower, as he pointed to the pattern on the wall of his shop.

Toys that last

Hall is clearly in the business of selling toys as much as making them. One of the reasons he started the side business, he said, was to promote the lumber he was selling at Anderson-Tully in the 1970s and 80s.

“I’m fourth-generation in the woodworking business, so I’ve been around it all my life. That was part of it. I was trying to promote the Southern hardwoods that we were selling,” he said.

That said, he does admit it makes him happy when a longtime customer asks him to build a new toy for their child or grandchild and amazed when an old one resurfaces. Customers will occasionally call to replace the moving parts of the toys that wear out, such as elephant trunks or crawfish tails.

“I met Bertram Davis (the great-great-grandson of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis) a while ago. I sold him one in 1985 in Dallas, and he ends up living in Vicksburg with one of my toys,” Hall said with a laugh. “Most people won’t throw them away. They’ll donate them to a church or something like that. It ends up having sentimental value to them.”

There is also sentimental value in the craft of creating a Tully Toy. He said all of his grandchildren have one, but they were not made by him. Their parents, Tully’s children, made them for their own kids.

“All of my kids can make them or have made them,” Hall said.

Hall is also thankful, he said, for the people who have enjoyed Tully Toys for nearly a half-century. He is a longtime member of the Craftsmen’s Guild of Mississippi, a statewide organization that works to preserve, promote, market, educate and encourage arts and crafts in the state.

Hall’s membership in the organization has given him an appreciation for how difficult it can be to make a living as an artisan, and he said he was thankful to have found an audience for his work.

“I’ve seen some really talented people in different parts of the country that have a hard time selling what they make. It’s hard that’s it’s not better appreciated,” Hall said. “I was fortunate to have a real job and do this as a hobby, and I was successful at my hobby.”