The City’s Lifeblood: When Vicksburg lost the river, they built another one

Published 3:11 pm Monday, March 21, 2022

All along the Mississippi River, the oxbow lakes and cutoffs tell tales of its centuries of wandering. Ghost towns like Rodney and Grand Gulf, which were left high and dry when the river changed course, are a testament to its fickle cruelty.

When the river shifted on Vicksburg, however, its residents didn’t fade into history.

They built another river.

The Inevitable Happened

In the decade-plus between the famous 1863 Civil War battle in Vicksburg and the nation’s centennial, it became apparent that Vicksburg had a big problem brewing.

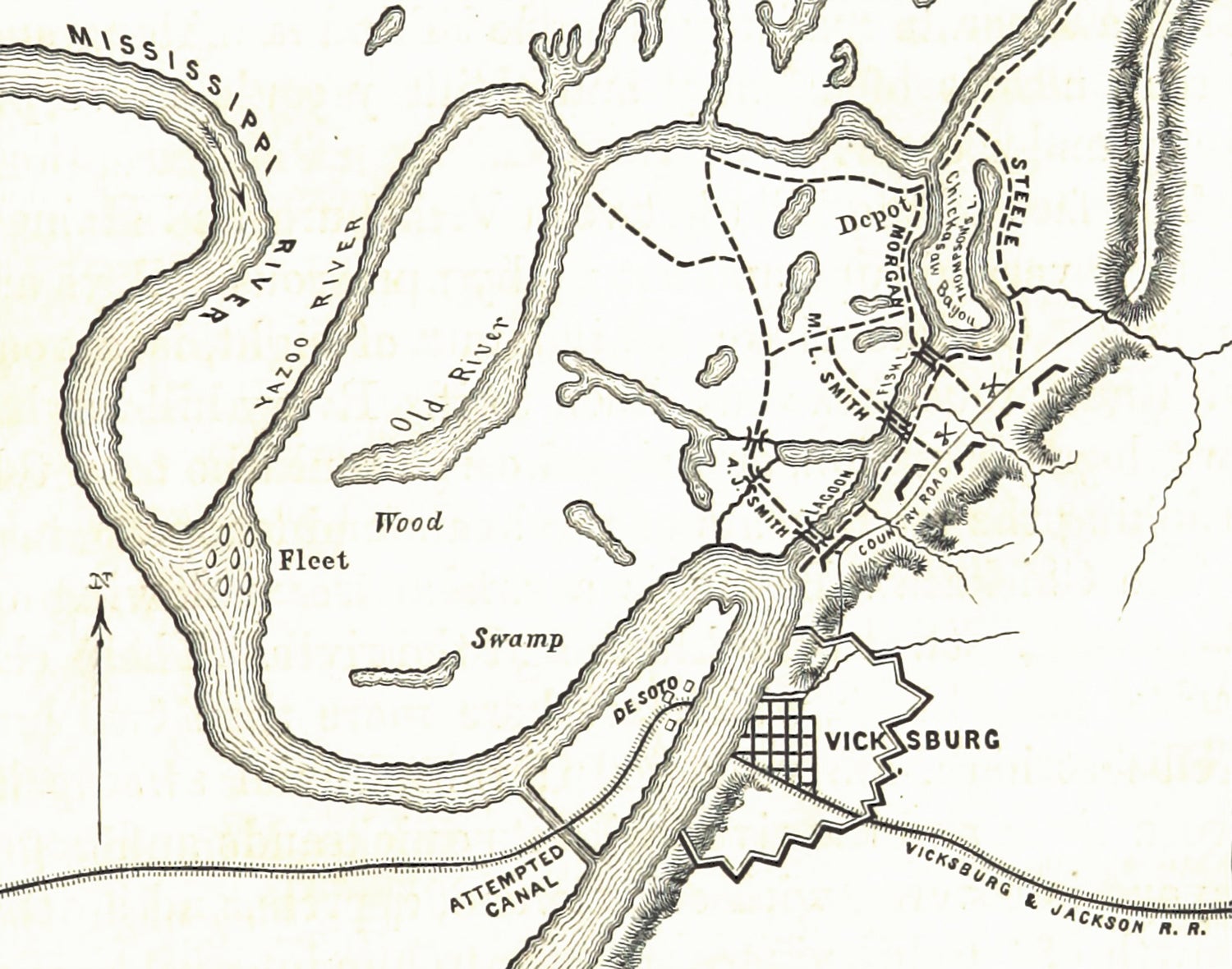

The Mississippi River at the time made a 2.5-mile wide horseshoe bend just north of Vicksburg, with the city’s bustling waterfront located on the southern leg. The Vicksburg Bend, as it was known, was what had made the city such a strategic location during the Civil War.

By 1870, however, local groups expressed concern that the river was cutting its way through the narrow peninsula between the two legs of the horseshoe. When it made its way through, it would likely leave Vicksburg several miles away from the river that was its lifeblood.

The inevitable finally happened on April 26, 1876. In the late morning hours, the river started to move through the peninsula known as DeSoto Point. Just after 2 p.m., it cut through the last bit of dry land with a rush.

“In the morning the river was about stationary, and would probably have remained so, but 10 minutes past two o’clock, the last link that held the peninsula, opposite the city, gave way, and the water came rushing through in a torrent,” the Vicksburg Herald reported. “The little cross levee, about 50 yards long, dropped into the river all at once, and opened up a passage for the water through the peninsula, and left an island on the upper side.”

The river’s latest wandering moved its course to its present location, which passes the southwest part of Vicksburg several miles away from downtown. The old river bed remained navigable for a time but was soon filled with silt and sediment that prevented boats from reaching the waterfront.

A private landing at Kleinston, on the city’s southern edge at the foot of Mattingly Street, was only usable during high water periods, and it was quickly apparent that the city’s future depended on coming up with a radical solution.

Restoring Vicksburg’s Lifeblood

Within a year, a plan to reconnect the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers — the latter had also been cut off by the course change — was hatched.

In June 1878, Congress appropriated $84,000 to the Board of Engineers for the first phase of the project.

Additional phases included:

• Stabilization of the river at Delta Point to prevent further movement of the river to the south.

• A bar dike to prevent mud from filling Vicksburg’s harbor.

• Dredging the former east channel to keep it open.

• Diverting the Yazoo River from its natural mouth upstream of Vicksburg to the north end of the former Vicksburg Bend so it would flow past City Front.

Work continued throughout the 1880s as funding came and went. Finally, in 1892 Capt. J.H. Willard of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers submitted a formal plan to Congress that laid out an exact route for a canal connecting the two rivers.

Dredging began in earnest in 1895, under the supervision of Willard’s successor T.C. Thomas, and over the next seven years, 7.5 million cubic yards of earth were moved to create the 9.2-mile channel. The dredges cut through six miles of soil to reach the Yazoo River about two miles west of where Steele Bayou joins it.

The project cost $1.25 million — $345,000 for survey work and $905,000 for construction — and work was done by the Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific Company. It was completed early in 1903, but low water prevented the new canal from being opened for several weeks.

A Day of Rejoicing

Canal Day — Jan. 28, 1903 — was a day of celebration in Vicksburg.

A dedication ceremony was held at the Walnut Street Theatre, followed by a steamboat parade up and down the newly christened Yazoo Diversion Canal. The festivities were wrapped up by an hour-long fireworks show that night.

Vicksburg, unlike some of its fellow river cities, did not wither and die without the Mississippi’s water flowing past. Some merchants adapted by shifting their operations to the new riverfront on the south side of town, and its population actually grew in the 1880s and 90s.

The opening of the Yazoo Diversion Canal, however, provided the city with an invaluable asset for future generations.

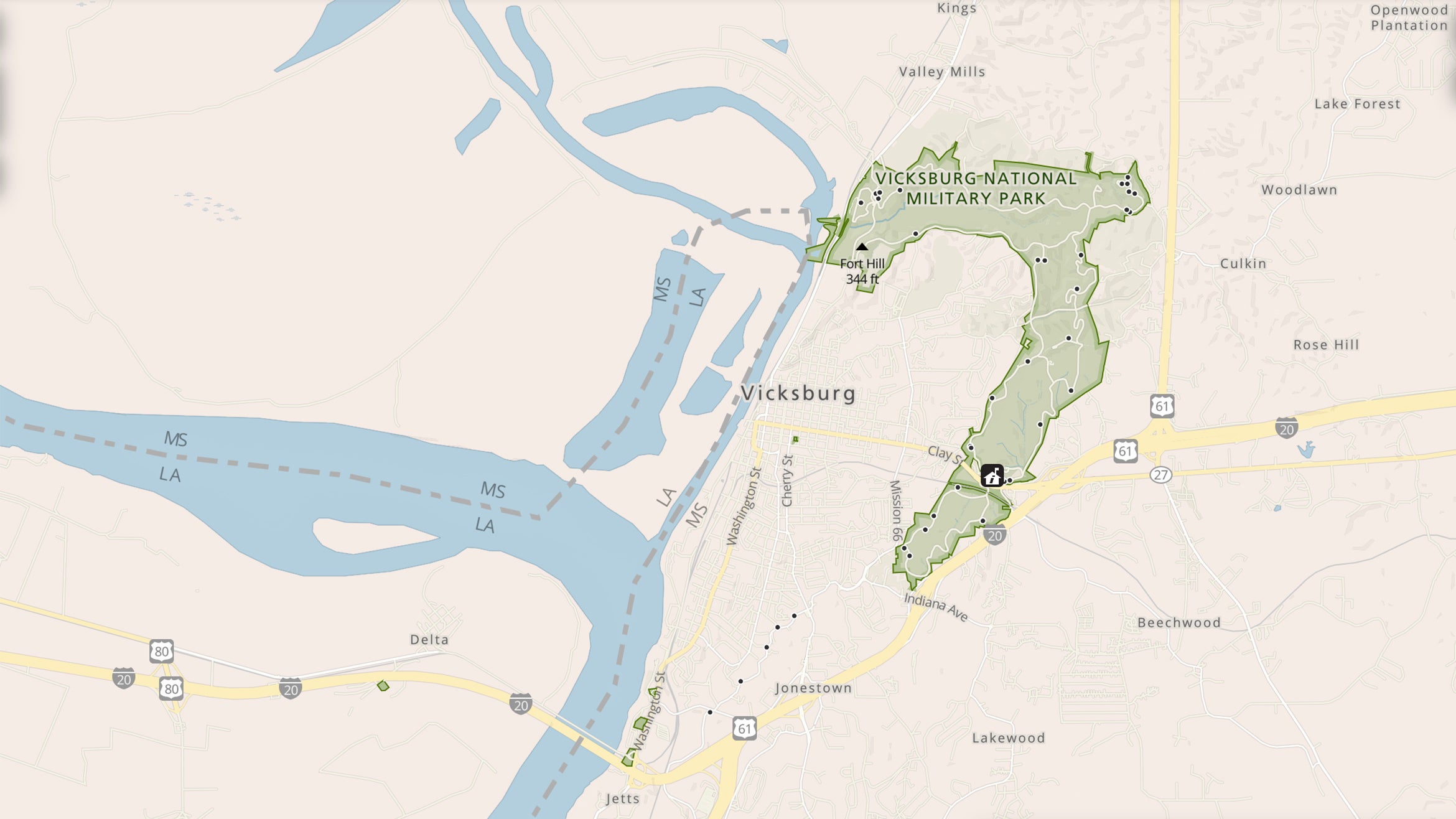

The Port of Vicksburg opened on the Canal in 1961 and today employs 2,200 people who move more than 14 million tons of cargo through it each year.

The Canal also provided river access to downtown. Cruise ships use it to bring tourists to Vicksburg, and it has become one of the city’s defining features.

Although the Yazoo Diversion Canal is not actually the Mississippi River, it once again made Vicksburg a river town.