HIDDEN IN THE BLUFFS: Life, Death and the business of Caves in Vicksburg

Published 9:43 am Saturday, February 25, 2023

Mississippi writer David Cohn spawned the phrase, “The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg.”

This is evidenced by Vicksburg’s rolling hills and bluffs perched high above the Mississippi River.

And it was these bluffs, rich in nutrients from their loess soil, that attracted the early 1800s settlers from the east.

“Its silt-sized particles (from the bluffs) allowed for easy access to water for plants and it drained well making it easily ready for plowing and spring planting,” the Vicksburg National Military Park website reads.

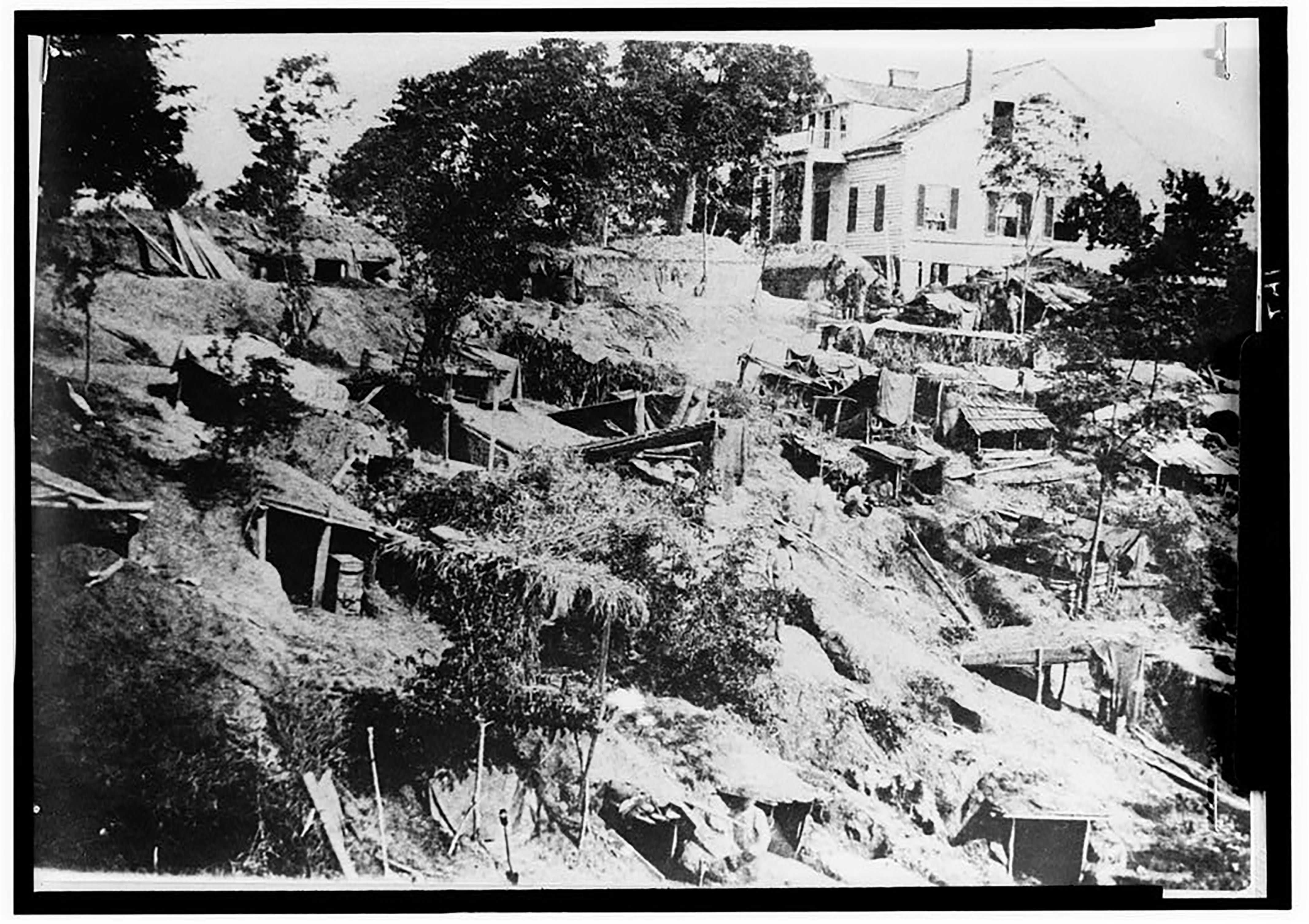

Loess soil also remains stable when cut vertically, making for a unique terrain that was used by both the Union and Confederate soldiers during the Siege of Vicksburg. This physical feature allowed soldiers to construct trenches that provide shelter from cannons and artillery.

Caves could also be constructed in the loess soil, which is what many of the townspeople did during the Siege.

Death, Life and the In-Between

In the July 1, 1963, Vicksburg Post anniversary edition, a story was written on cave life during the Siege titled “Birth, Death: Great Drama In Cave Life.” And in the story, an account, which is said to have been one of the “few published,” was given by Mrs. James M. (Mary) Loughborough, on cave life in Vicksburg.

Loughborough describes her cave as an “excavation in the earth the size of a large room, high enough for the tallest person to stand perfectly erect, provided with comfortable seats and altogether quite a large and habitable abode.”

She explained further that the rooms were arched and braced, and these supports took up most of the room in the confined quarters.

“The cave was in the shape of a T,” Loughborough said, wherein one of the wings was the bed, and the other a dressing room. Mattresses had been dragged in for beds, she said, and mirrors and pictures adorned the walls. Loughborough said her cave also had a “tent fly that was stretched over the mouth of the cave to shield those inside from the sun.”

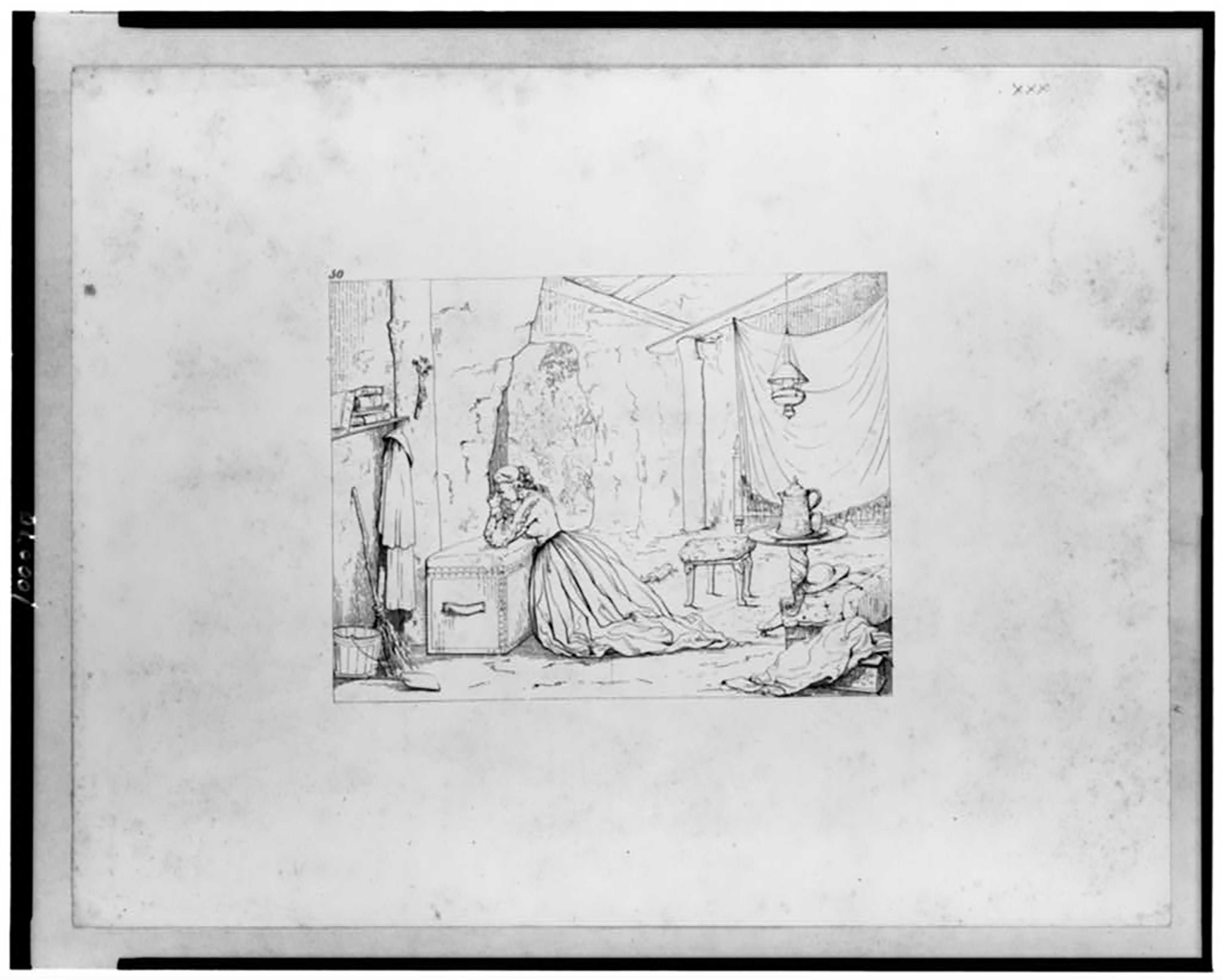

Days were endless sitting “idle” in the caves, she said, which was reiterated in Virginia Calohan Harrell’s book, “Vicksburg and the River.” Harrell writes of a survivor who shared their account of cave life with Mark Twain on how boring it had been living in the cave.

“It got to be Sunday all the time. Seven Sundays in the week, to us anyway. We hadn’t anything to do and time hung heavy,” the survivor told Twain.

And while the caves were constructed to serve as protection against the bombardment, they were not foolproof. There was still the possibility of them giving way and live ammunition breaching the shelter.

Loughborough said one mother during the Siege had taken her child into the cave where she thought he would be safe. But that was not the case in this situation. A mortar shell came rushing through the air, she said, “And fell with such force that it cut through into the cave and crushed in the head of the sleeping child.”

Another instance saw new life brought forth in the caves. During an intense bought of shelling, the wife of Duff Green (for whom the mansion is named) birthed a son in a cave. She named her baby William Siege Green.

A dirty business

Cave life was an opportunity for some entrepreneurs.

In the same Post article, Dr. Peter Walker said, cave building was a “big business with set prices depending upon the size and elaborateness of the excavation.”

“For $20, a simple one-room affair could be dug. A deeper thick roofed, several-chambered cave, shored up by timber and with shelves cut into the earth, cost $50,” Walker said.

Caves could also be rented.

Some people preferred to rent.

“Mrs. M.L. Powell, whose comments on the Siege ran in The Post in 1934, recalled that her family rented two caves, one where the post office now stands and the other on Grove Street.” The article referred to the former U.S. Post Office building on Crawford Street, which is now vacant.

As stated in the story from July 1, 1963, “No tales of the Siege of Vicksburg had more drama, perhaps, than those recounted by the men, women and children who spent those 47 days underground in a cave.”