Life Beyond Loss: Branch writes memoir on overcoming tragedy after Eagle Lake incident

Published 10:10 am Thursday, September 21, 2023

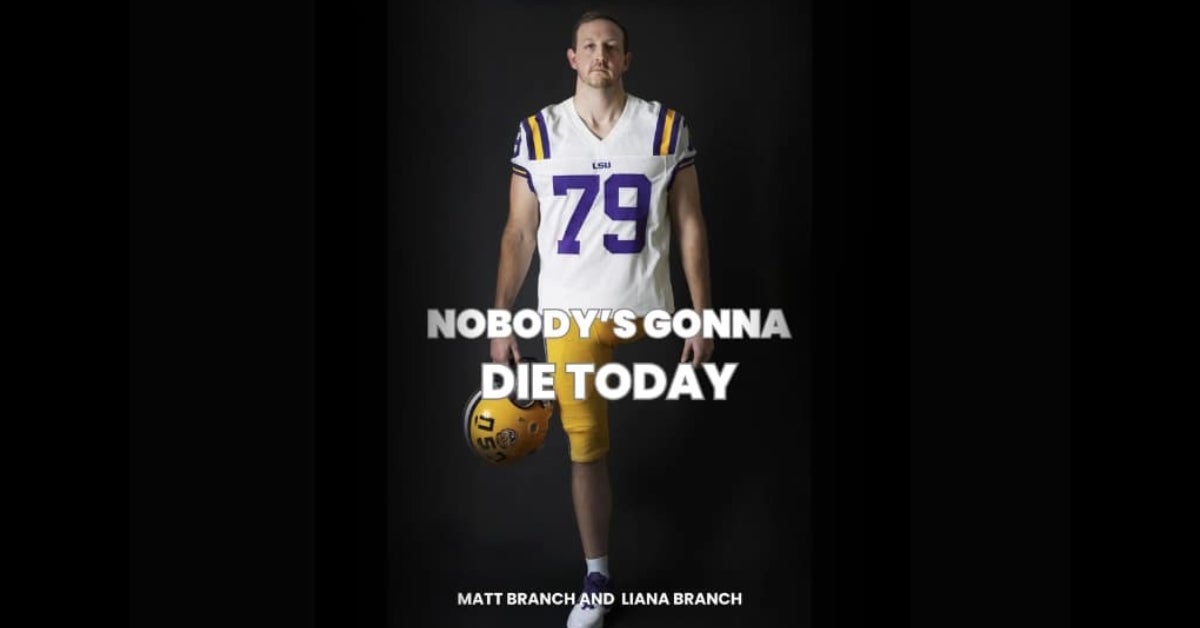

- Matt Branch almost lost his life and did lose his leg in a hunting accident at Eagle Lake. How a gun, a dog, and faith turned his life around. (Photo Submitted)

The book Matt Branch wrote is about a former football player who lost almost half his weight but became twice the man.

He titled his personal memoir “Nobody’s Gonna Die Today,” but Branch did die, after a hunting accident that cost him a leg. In the aftermath, the accident changed more than his body; it also changed his mind, about what is important in life and how that life should be lived.

During much of his journey of recovery and discovery, Branch was accompanied by healthcare professionals at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Merit Health River Region in Vicksburg and Methodist Rehabilitation Center.

“One day in June of 2020, I had been depressed, wondering what was the meaning of life,” said Branch, 34, of Monroe, La. “I had a spiritual experience. I came home, sat down at my computer and started typing.

“I typed for four days straight, and then I had a book — 60,000 or 70,000 words,” he added. “I sat on it for three years. I didn’t know if people would read it. Then, I decided to take the chance.”

Co-written with his wife, Liana Branch, the book features a foreword by Tommy Moffitt, Branch’s strength coach at Louisiana State University.

“Coach Moffitt used to say during practice on 100-degree days, ‘Keep running, nobody’s gonna die out here today,’” Branch said.

Those words became the title of a story that begins with a dog and a gun. Three days after Christmas in 2018, Branch went on a hunting trip with his younger brother, cousins and friends.

The outing at Eagle Lake in Warren County was an annual custom, but when Branch got up that morning, “I had no idea this would be the last time both my feet would hit the floor for the rest of my life,” he wrote.

Branch’s legs helped pay for college.

Brought up in Rayville, La., near Monroe, he was a star high school football player, good enough to win a football scholarship in 2008 to LSU. A 6-foot-6 offensive lineman, Branch played in almost 30 games for the purple-and-gold, but says he could have worked out in the weight room more, paid more attention to learning plays and attended class more. Four years in, he was injured and his career was done.

He had a job, though, in his family’s hometown agricultural business, and time to go deer and duck hunting, which he loves.

But the adventure at Eagle Lake was an unfunny, slapstick tragedy on a cold, wet day that got wetter when Branch flipped his ATV and was pinned, for a while, underwater.

Later, reunited with the duck-hunting party, he placed his 12-gauge Beretta in the bed of a Polaris Ranger. Tito, their hunting dog, jumped up in the utility vehicle — and onto the loaded shotgun.

“We heard the shot go off,” Branch said. “We didn’t really understand what it was for a split second, then I saw a hole in the Ranger where the shot went through.

“I didn’t feel any pain, but I stepped back to see if I was hit or not; then I couldn’t feel my leg,” he added. “It hit me in the top of the left thigh and groin area, and it went through the Ranger bed first, so it blew pieces of plastic and a metal mojo [decoy extension] pole into the wound. It destroyed my femoral artery. My muscle was shredded. I fell down and my blood pressure dropped. I could barely keep my eyes open.”

His best friend applied pressure to the wound to slow the bleeding which, Branch believes, was already slower because of his accidental head-dive in the cold water.

Rather than wait for an ambulance there, his buddies drove him to a highway that was easy for first responders to find. In the meantime, he had the sensation of “being constantly on the verge of falling asleep.” That’s what dying felt like to him.

Volunteer firefighters from Eagle Lake applied a tourniquet to his leg. On his way to the Vicksburg hospital, his heart stopped beating. Branch had to be revived more than once.

“The doctors in Vicksburg and the paramedics estimated that I was in cardiac arrest a total of 45 minutes that day,” he said. “They did everything they could to stop the bleeding, to keep my heart working and keep me alive.”

From Vicksburg, he was airlifted to UMMC, where surgeons tried to save the leg, but, mostly, his life.

“He lost all blood flow to the leg,” said Dr. Ian Hoppe, associate professor of plastic surgery at UMMC. “It needed to be cleaned out continuously.”

Hoppe would participate in six surgeries for Branch.

“It’s very unusual to have to take the entire leg up to the hip,” Hoppe said. but that’s what they did. The tissue was so damaged, Branch’s leg couldn’t be saved.

For 12 days, Branch was in a medically-induced coma. When he awoke, he showed signs of post-traumatic stress. But his family was there to encourage him and pray.

“His life was preserved by constant medical intervention,” Liana wrote. “The nurses used a marker to write on a glass wall in the room to keep a count of the units of blood Matt had been given. To be transparent, a unit of blood is equal to one pint. The wall was covered in marks in three days.”

As he improved, nurses in the ICU came to his room to watch football games with him and bring him purple popsicles.

“They treated me like a human being, not a sick patient,” Branch wrote.

Branch spent more than 40 days at UMMC, then about two weeks at Methodist Rehab, where he met Dr. Hyung Kim.

Kim, also an assistant professor of neurosurgery at UMMC, is a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation. But, at Methodist Rehab, he has seen few cases where a patient loses an entire limb, he said.

“In which case you need an entire prosthetic limb. This type of amputation is much more difficult when it comes to training the patient to learn to walk,” Kim said. “Mr. Branch was young, though, and in good shape. He was motivated and worked hard.”

Today, Branch shares his story. He also swims, lifts weights, rides bikes and does cross-fit training.

He does this on a titanium prosthetic leg, borne up as well by his religious faith, “brave and fearless” Liana and the love of their two young children.

At one time, he weighed 305 pounds. Now, at 165, he has lost a lot of weight, but “found purpose.”

“Before the accident, I was more focused on material wealth, being impressive with a career, all the things that the world offers,” he said. “When I was laying on the side of the highway thinking it was over, I didn’t care about any of that. What I cared about was truth, and family and friends, what impact I had on their lives.

“That’s what matters — what you do, not for yourself, but what you do for others.”