REMEMBERING THE STORM: Post’s coverage of 1953 tornado earned journalism’s highest award

Published 11:16 pm Friday, December 1, 2023

Over the years, people have become accustomed to seeing news as it happens.

But in 1953, the multi-media people now take for granted didn’t exist. Television was still in its infancy and the computers that would one day bring social media were still experimental.

So when an F5 tornado struck Vicksburg, the only source of information available immediately after the storm was the rumor mill, which painted the effects of the recently passed storm as worse than it was.

When then-Publisher Louis P. Cashman Sr. realized the Vicksburg Sunday Post Herald — known today as The Vicksburg Post — could calm fears and provide accurate information, he and his staff set to work getting out in the city to get the facts. The paper’s efforts in reporting the storm would win it the greatest award in journalism, the Pulitzer Prize.

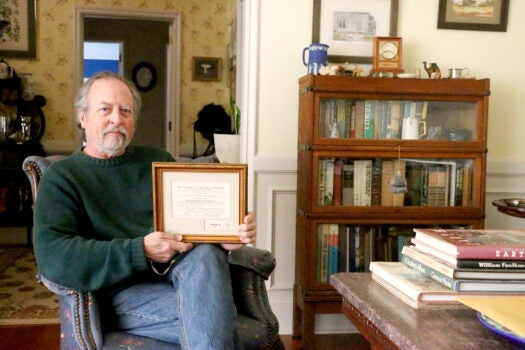

“We were nominated for the award,” said Pat Cashman, the grandson of Louis P. Cashman Sr., who served as publisher of The Vicksburg Post from 1985 to 2013. “A number of people nominated the newspaper for the Pulitzer for deadline reporting.”

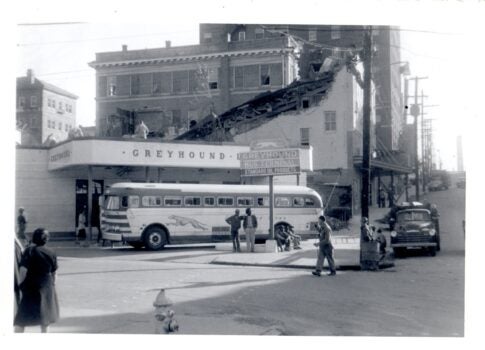

From the time it touched down about 5:31 p.m. in eastern Madison Parish west of the Mississippi River until it ended about 5:40 p.m. north-northeast of the city, the Dec. 5, 1953, Vicksburg tornado traveled 7 miles, cut a path 500 yards, killed 38 people, injured 270, left 1,200 people homeless and caused $25 million in damage (more than $288 million in today’s money).

In its wake, the storm left damaged and collapsed buildings, broken water and gas lines and downed electrical lines, making conditions extremely difficult to publish a paper.

Even more unusual, however, was that the staff at the paper was unaware of what was happening just blocks away from the paper’s building at the corner of Cherry and South streets.

“We were three blocks up,” Cashman said. “A lot of people in the building didn’t even know it. It was just a dark, heavy rain storm. I think Charlie Fog, who was editor at that time, came in and said, ‘you know what’s going on? Everything is damaged. All the town is torn up.’ It was Saturday afternoon and a lot of people (in the building) were getting ready for the Sunday paper. So many people just had no idea that four blocks away, there was a lot of damage.”

And the rumors and stories about the city’s condition started.

“The reports were coming in that thousands were dead and the whole city is destroyed,” Cashman said. “And you know, my grandfather said, ‘no, that’s not the case.’”

With reporters out getting information, other staff members prepared to print a paper under extreme conditions.

“Electricity was restored to the building, which was fortunate, but natural gas was cut off with broken pipelines all across downtown so we had no gas to melt the metal for plate casting,” Cashman said. “But Clyde Beasley was the head pressman, and he said, ‘I’ve done this before; I’ve printed through storms.’”

Beasley capped off the gas pipes for the paper’s large smelter to cast the big cylindrical plate for the press and the staff went out “and got every bag of charcoal they could put their hands on in town.”

“So he converted from gas heat to charcoal (to print the paper) so we were able to make all the plates. The linotypes were electrically operated.” Cashman said, adding staff members scooped up water from the ditches outside to develop film.

“So they, they got the paper out on time and distributed the Sunday Post-Herald,” he said. “There was no interruption of at all. We were able to put the Sunday paper, the combined paper out, and then again Monday morning both Herald and The Post were printed without any interruption.”

The toughest part that weekend, he said, was converting the equipment to go to charcoal to make the pressed plates.

“Everything was hot metal,” he said. “You had to melt all of the metal and cast it and make the mats and then the plates. Without the gas .. a lot of people who would’ve said we’re done; we’re out of it. But we were able to convert to charcoal and kept the fire going. Literally.

“That was the biggest thing: Functioning, getting reliable, accurate information out in a timely matter. The tornado did not stop the newspaper from publication.”

The Pulitzer Prize, established by Joseph Pulitzer, who has been regarded as the most skillful of newspaper publishers, is an award that was founded as an incentive to excellence for achievements in newspaper, magazine, and online journalism, literature and musical composition in the United States.