Ironclad continues to amaze visitors

Published 12:05 am Sunday, June 1, 2014

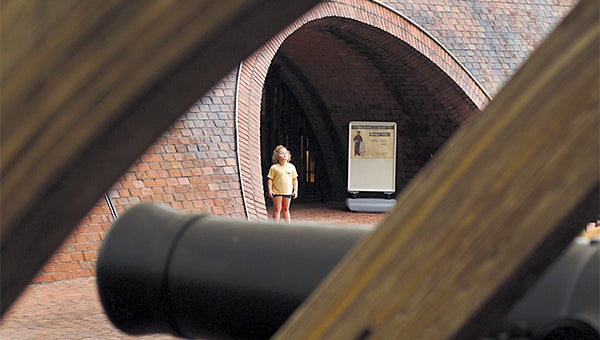

A young vistor to the U.S.S. Cairo museum looks in amazement at the shear size of the boat. Ralph Fitzgerald-The Vicksburg Post

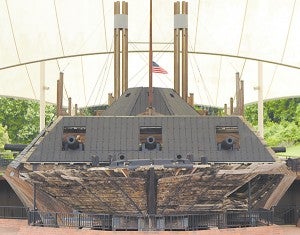

She went down in twelve minutes only to rise again to national prominence 102 years later and have her image stamped on the back of the U.S. quarter. Admiral David Dixon Porter, Commander of the Mississippi Squadron, marveled at not losing a soul during the sinking of the U.S.S. Cairo in 1862. Today, visitors walking the deck of the Cairo can only imagine how hard life was in the 1860’s, being a sailor aboard this state-of-the-art war vessel. Only the stench of gunpowder-fired cannons and your fellow shipmates overpowered the smells of coal burning in the tube boilers that provided steam power for the ship.

Every year hundreds of thousands of tourists from around the country come marvel at this magnificent Civil War gem. Preserved for over 100 years in the murky waters of the mighty Yazoo River, she was raised to the surface in three pieces, put back together like a jigsaw puzzle and placed on display in the Vicksburg National Military Park.

“Amazing. Simply amazing” stated Curtis Bergeron, of Tulsa, Okla., during his visit Thursday afternoon to the U.S.S. Cairo, a City-class ironclad gunboat constructed for the Union Navy by James Eads during the Civil War. She was the lead ship of the City-class gunboats, sometimes also called the Cairo class, and was named for Cairo, Ill. Cairo was the first ship sunk by a naval mine on Dec. 12, 1862.

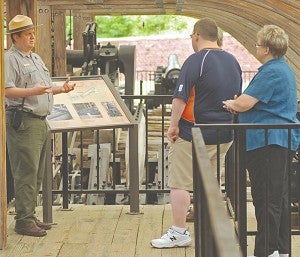

Inside the Cairo museum, a plethora of well preserved artifacts from the ship is displayed that includes cannons, muskets, knives, medical instruments, uniform buttons and many other items that the crew would have carried with them or used in the performance of their duties, giving you a glimpse into what life was like for the sailors at sea.

Plaques around the museum give visitors insight into the crew’s make-up, mostly immigrants. You might have heard Danish, French, Russian, German, and accents from Ireland, England and the Caribbean. This group of men came from many walks of life. They were black and white; they were farmers, teachers and butchers. Most of them had no sailing experience and learned their duties on the job. U.S.-born or not, these Union sailors were fighting for the survival of the country they called home.

A crew of 17 officers and 158 sailors worked and lived on the Cairo. The only living quarters onboard the ship was for officers. The crew slept in hammocks by their duty stations. The ironclad was 175-feet long and 52-feet wide and weighed 512 tons. She was armed with three 8-inch smoothbores, three 42-pounder rifles, six 32-pounder rifle, a 30-pounder rifle and a 12-pounder howitzer used to prevent the threat of boarding parties during riverine combat.

Searching for the Cairo and armed with an inexpensive compass, a wealth of historical information and an instinct for discovery, historian Edwin Bearss, together with Civil War buffs Warren Grabau and Don Jacks, set out in a small boat one cold November morning to locate the sunken ironclad gunboat.

When the compass needle deflected consistently over a single point in the river, a series of events were set in motion that would culminate in a massive salvage effort through which the Cairo would emerge from the muddy bottom of the Yazoo River to become one of the most popular tourist attractions in America.