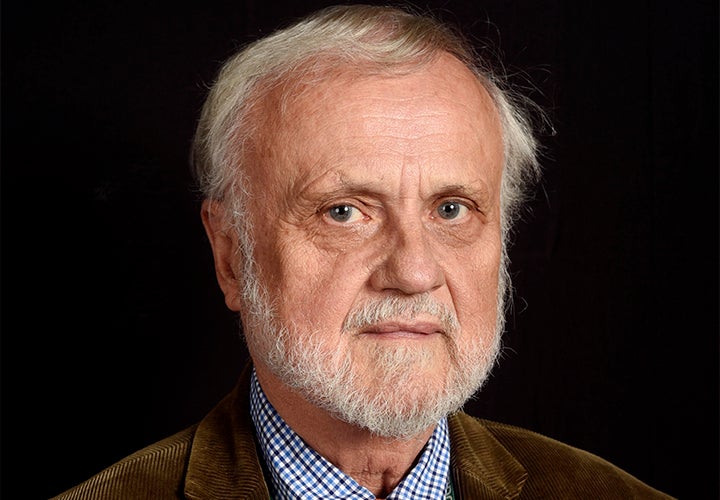

Briuer makes studying history a way of life

Published 7:37 pm Sunday, November 26, 2017

- (Courtland Wells/The Vicksburg Post)

Frederick Briuer has an extensive resume.

He served four years in the U.S. Marine Corps, has a Ph.D. in anthropology from UCLA, was the first full-time professional archaeologist to work for the Department of Defense, author and the retired director of the Center for Cultural Site Preservation at the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center.

He was the consulting archaeologist on the Kennewick man case, a 1996 dispute surrounding the discovery of an ancient skeleton in Washington State, and presently serves as chairman of the Vicksburg municipal Fort St. Pierre tercentennial planning commission.

He has an interest in military history and military emblems that led him to write a three-volume set of books devoted to U.S. Marine Corps emblems.

Briuer said it was his love of military history that led to him becoming involved in archaeology and anthropology.

“I enlisted in Marines at 17, got out and went to college on the GI Bill; I took my BA, MA and Ph.D. at UCLA in California, and landed a job with the US Army as one of the first archaeologists to be hired by the Army,” he said.

He spent 11 years as the staff archeologist for Fort Hood, Texas, before accepting a position with the Waterways Experiment Station (now ERDC) as its archeologist.

He said the Army brought in archaeologists to meet federal environmental and historic preservation laws requiring all federal agencies to take into consideration the archeological records they manage — a move requiring surveys and research and other activities.

Being an archeologist in the initial years, Briuer said, “Was pretty exciting. There was a lot of work to be done and I worked on many interesting projects all over the county.”

Later in the process, however, it became more difficult to get funding.

“My job was to find ways to comply with the law that were more cost effective and more efficient, and that didn’t have a priority, unfortunately. The last few years were rather stressful,” he said.

The projects, he said, involved using geophysical techniques like ground penetrating radar, geographic information system development to survey the federal lands and determine areas of historic significance. GIS, he added, is an ideal tool for managing complex databases.

“I also did some field investigations and excavations.” And that led to his involvement with the Kennewick man.

The case involved an archeologist who found the skeleton of a man and dated it at 9,000 years old using radiocarbon dating.

“American Indians protested and demanded that the remains be repatriated to them,” Briuer said. “The archaeologists — 10 of them — sued the Corps, claiming the skeleton was highly significant and under the law is required that it be further studied.”

The archeologists, he said, won, and were able to study the remains, despite the protests of some Native American groups.

“It’s of great satisfaction to me that the judge who ruled in favor of the 10 archeologists, cited my research about seven times,” Briuer said.

Briuer retired from the Corps in 2003, and spends his time doing research and writing, which led to his three books on Marine Corps emblems.

“As a kid, I would get military insignia from the G.I.s returning home from World War II. One of the first things they would do is throw their uniforms away, and I would make it a point to go around and collect the patches and the stripes and the pins, so I got interested early in on that,” Briuer said.

“When I enlisted, I was issued emblems. My dad had given me his emblems from World War II and Korea. So I had a good collection going, and all of a sudden, they started getting very expensive, and I realized, ‘I can’t afford to collect these things.'”

With the prices being so high, Briuer decided to combine his interest in emblems with his archaeological training and research background to do a book on the subject, because, he said, “The literature is very sparse. There are only three books on the subject in print right now.”

He worked with museums and private collectors across the country to allow him to photograph and describe the emblems.

“My favorite ones are the ones that have an archeological context, because of all these hundreds of emblems that have survived the last couple of hundred years, many of them come from surplus sales and they are sold to the public from the government and then they’re sold over and over again and in and out of collections, and you don’t really know the story when it’s that mixed.”

He showed a photo of a Marine Corps emblem displayed at the Cairo Museum at the Vicksburg National Military Park.

“It was in a sailor’s locker box. There were no Marines on the Cairo. And how that got to be in the sailor’s locker box is amazing, because along with the emblem and what was left of the hat were five pocket knives, each with different initials. So it suggests that sailor was either a good gambler or a thief or both.”

He also discussed the discovery of Marine emblems in the wreck of a Navy ship that sank in a storm off Cape Hatteras, N.C., in 1876 and killed 100 sailors and Marines.

“Divers dove on that wreck and recovered Marine Corps artifacts, including very rare eagle, globe and anchor emblems. Vey rare.” The emblems are now at the Marine Corps Museum.

There are also Marine emblems found at French battlefield sites and Marine encampments. All those emblems, Briuer said, were made in France.

Besides displaying the Marine Corps emblems from 1804 to World War I, he said, his first book also discusses fakes and forgeries that are on the market to inform and caution people who are collecting emblems or investing in them. His second book includes emblems from 1919 to present, while the final book covers the prices paid for emblems and the number of them sold.

He said it’s taken him 25 years to compile the information for the books.

His background in history and archaeology are also being used as he heads the nine-member commission planning the observance of the 300th anniversary of Fort St. Pierre, which was a French settlement near the Yazoo River. The fort, he said, was built in 1719.

“We’re looking at developing a wish list, applying for grants, tying to raise the level of awareness of the general public about the importance of our national historic landmark site,” Briuer said.

“There are only two designated national historic landmark sites in Mississippi for that French and Indian period, and that’s Fort Rosalie in Natchez and Fort St. Pierre in Warren County. We want to raise the level of awareness of what we have here. We’re trying to get exhibits in the local museums to let people know about the French and Indians, a very interesting period; only 30 years.”

The group hopes to begin the observance Jan. 1, 2019.

He also plans to work on a family history and write about his grandfather’s village in Russia, which he visited in 1995.

“I would like to put in a book, but these three (on emblems) will keep me plenty busy,” he said.